For better or worse, there is only one person in the world who thinks of me as a baseball player. And it is not I.

Joe Stephan was the ace winning pitcher on our little league team, the Wantagh Panthers. I was on that team for three years, but it was during the second year that I was Joe’s catcher. It was also the year that we won the World Series in our division. That’s what they called it.

After that winning season, Joe was elevated to a higher division in the league while I stayed with the Panthers, moving from catcher to the infield. I was an average player at best, able to execute a play here or a hit there. Most of the other kids on the team were younger (and worse players) than I was. I do remember one particular play where I cleanly fielded a grounder at third and threw out the kid running to first. Since it happened so rarely, it’s burned in my memory.

Each year the Little League held a fundraiser, and kids would go to work selling subscriptions to our hometown newspaper, the Wantagh Citizen. A photo of a happy homeowner (who’d just purchased a subscription) standing next to me in my Wantagh Panthers uniform appeared in the paper, and I was forever immortalized as a ballplayer in the news media. Sadly, no copy of that photo appears to have survived. (Immortality can often be brief.)

That was the last year I played Little League baseball.

Not so for Joe, who was a really good player and went on to play in high school.

Joe’s family managed the Bide-A-Wee Home and Pet Cemetery located directly across the street from Wantagh High School, where we both attended. The Bide-A-Wee’s claim to fame is that it is the final resting place of Richard Nixon’s dog, Checkers. Nixon’s 1952 “Checkers speech” is legend. (Nixon himself is also a legend, but for reasons separate from his dog.)

My high school classmate and former battery-mate Joe ran in more Catholic circles than I. He married another classmate, Eileen. I’ve recently been in touch with him, and he wrote that they’d been married 50 years. They didn’t go far from home and still live in Long Island.

I remember with clarity meeting Joe at our ten-year high school reunion.

“That was one incredible team we had back then, wasn’t it?” he smiled as we shook hands.

I smiled back and agreed. “Incredible.” Much of life is about perspective.

At the time of that conversation I was in my third year of graduate school at UC Berkeley and baseball was light years in the past. We’ve had a similar conversation at every reunion since. Joe continued to coach Little League baseball for many years, and I’m sure he was a wonderful coach.

I’ve always thought fondly of Joe. He’s a good guy—I liked and respected him then, and still do. And of course, he’ll remain the only person who ever thought of me and baseball in the same sentence.

Like my parents, I was born in Brooklyn, NY, with the result that for many years my family members were Brooklyn Dodgers fans until the venal owner, Walter O’Malley, moved the team to Los Angeles in 1958—this despite the Dodgers being the most profitable team in baseball from 1946 to 1956. Incapable of rooting for the Yankees, we all became Mets fans in 1962 when that inaugural/expansion team posted a record of 40 wins and 120 losses, the worst regular season record in modern history. My fellow Mets fans and I became accustomed to rooting for a team that never finished better than second-to-last until the “Miracle Mets” beat the Baltimore Orioles in the 1969 World Series, still considered one of the biggest upsets in World Series history.

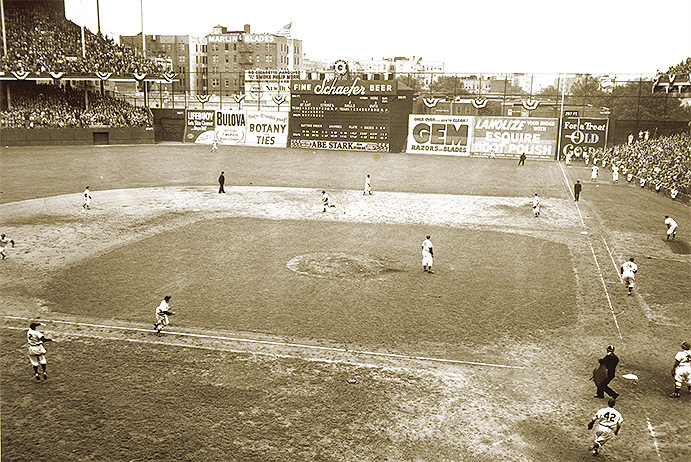

Sometime in the mid-1950s, at my insistence, my father brought me to Ebbets Field to see the Brooklyn Dodgers play. Although I wasn’t familiar with the term “nosebleed section” at the time, that’s where we sat; my already limited kid’s-view of the field was further obstructed by a pole holding up the tier above us. The men around me were all smoking cigars or cigarettes. Those are the things I remember. I have absolutely no recollection of who won the game. (In my fantasy, Brooklyn played the St. Louis Cardinals and I saw Stan Musial. Maybe it really happened.)

I went to Shea Stadium to see the Mets play a couple of times, but left for college in Boston in 1964. At that point I had little time in my life for baseball.

But prior to that I’d play pick-up baseball games with friends, or softball at school or when I went away to summer camp. In spite of not being a particularly talented player, I knew the game well enough and felt comfortable throwing the ball around the infield, sliding into base, and standing in the batter’s box. I was a wiry kid and ran fast. I was never teased and was never chosen last. (I suppose we tried to act like the major leaguers we saw on TV, but it wasn’t until years later that kids emulated the pros more carefully and began to spit at every opportunity.)

In spite of my growing up with the game, I remained naïve about its deeper intricacies. This became apparent one summer at camp during a game I recall well. There were two 14-year-old kids in my bunk who were close friends and competitors. One was playing on my team and the other was on the opposing team. Our guy was pitching, and he was good. But when his friend came up to bat, he called a time-out. He then ran out to left field and gave the ball to the left fielder, who ran to the pitcher’s mound. Neither player was leaving the game; they were just exchanging positions, which is permitted.

On the first pitch, the batter hit a towering fly to left field. Waiting under the ball was his good friend and competitor. After making the out, our guy ran back to the mound and pitched the rest of the game. He knew exactly where his friend was going to hit the ball. I was amazed. (I never much liked the guy—he had an ego the size of Yankee Stadium. But I was impressed.) This was a much higher level of baseball than I’d ever played, and it was just a summer camp softball game.

As an aging adult I became cautious about playing baseball because of what I refer to as Little League Syndrome (I coined this phrase, so please credit me when you use it, as I’m sure you will). I define the syndrome as the mistaken belief that while it may seem perfectly natural to pick up a bat and stand at the plate waiting for the pitch, you must not forget that you are now in your fifties (or you’re a 70-year old grandfather) and you are not going to beat out that slow grounder as you race toward first base. And even if you do, you’ll pull up with a torn Achilles tendon. Or you’ll break your hip sliding into second, or get hit in the groin attempting to field a hot grounder, or tear your rotator cuff throwing the ball to the cut-off man. You may still be 16 in your mind, but your body is now that of an old man, you stupid idiot.

(Not being a girl, I’m unaware of a similar syndrome that women suffer. But I would not be surprised if there is.)

While certain exceptional moments in our childhoods can result in lasting peak memories, there are incidents that can leave a person with both bad memories or emotional scars. My father, a World War II Army Air Force veteran and successful independent businessman, once told me that when he was visiting a client in a Manhattan office building he ran into an acquaintance from high school. They hadn’t seen each other for decades. Although a cliché, they were indeed standing at adjoining urinals in the restroom.

This guy says to my father, “I know you. You’re from the old neighborhood in East New York.”

My dad looks over and recognizes him. “Yeah. I think we played baseball together.”

“That’s for sure,” says the other guy as he zips up. “You’re the kid who dropped the ball in that big game.” Then he left the bathroom without another word, hopefully washing his hands first.

As my dad told me the story, he did not seem particularly upset or bothered. I always wished that I could let those kinds of slurs and bad vibes wash over me as easily as he did. But he survived WW2, and I hadn’t been born yet.

I moved to San Francisco in 1969 and two years later moved across the Bay Bridge to Oakland. It was an incredible time for the Oakland Athletics baseball team, which won the World Series three years in a row: 1972, 1973, and 1974. Such were the vagaries of baseball at the time, and particularly the Athletics team, that you could walk up to the Coliseum box office to buy a ticket for that day’s World Series match. But I was busy in grad school at the time, and while I’d become a fan, I was not a major fan. Regardless, it’s always fun rooting for a winner. (I hadn’t played baseball for years. Mostly I played volleyball.)

In the 1980s, after I’d divorced and moved back to California from Maryland where I’d taken a job after graduation, my son Adam would visit me during his summer vacations. He was in day camp while I was at the office, and that worked great. But what about evening activities?

By a strange and wonderful coincidence, the 1987 All-Star game was scheduled to be played in Oakland. Promotional notices began to appear announcing that if you bought an Oakland A’s season ticket you would be eligible to buy an All-Star Game ticket. So I bought two 20-game season ticket packages and exchanged some of the tickets so that virtually all 20 games coincided with the six week period that Adam would be visiting.

We spent so much time at the Oakland Coliseum that I should have just brought some pillows and blankets and lived there. When the Athletics were in town for a weekend series it was not unusual for us to be at games on Thursday, Friday, Saturday, and Sunday. We’d arrive early for batting practice and stay until the bitter end, with Adam seeking autographs from icons such as Jose Canseco, Mark McGwire, Dennis Eckersley, Reggie Jackson, Dave Stewart, Rickey Henderson, Carney Lansford, Dave Parker, and manager Tony La Russa. When you are immersed in the game, you tend to know everything about the players, including the names of the players’ wives (and who was pregnant), whose father had a heart attack, or who’d gotten a speeding ticket. It’s very weird, really.

Future Hall of Famer Reggie Jackson was one of our favorite players. His brother, James Jackson, was a patient of mine at the time—he was dating one of my co-workers.

One afternoon Adam and I were driving past Gold’s Gym in Berkeley and I saw Reggie walking toward the entrance to gym. I pulled over.

“Adam, there’s Reggie. Roll down the window.” I didn’t have power windows in that car.

Adam freaked out. He was too much in awe to intrude on Reggie. “No way, Dad!”

“Adam, open the window!” Our opportunity to greet him was diminishing as Reggie neared the gym.

“No, Dad!”

“Adam,” I said with infinite patience, “Open the damned window!” He did.

“Hey Reggie!” I called. “How’re you doing?” He stopped, walked over to Adam’s window, and leaned down so he could see us. I told him, “I’m the eye doctor around the corner, and your brother James is a patient of mine. This is my son, Adam. We’re big A’s fans.”

Reggie smiled and was as friendly as could be. He told us he was on his way to work out.

Adam learned a big lesson that day, and years later told me a story of how he’d managed to talk his way into a meet-up with the Athletics’ broadcaster at the Cincinnati Reds stadium when Oakland played an interleague game there.

God is obviously a baseball fan and was watching over Adam and me. The Oakland Athletics won the American League pennant in 1988, 1989, and 1990. Managing to have Adam attend all three of those World Series required special domestic negotiations with his mother (my -ex). For some unfathomable reason she thought it was more important for him to attend school than the World Series. But he convinced her and managed to be at most of the home games. He also racked up a lot of frequent flyer miles in the process.

Sadly, the Oakland team lost the World Series in 1988 and 1990 despite their tremendous success during the regular season. After the loss in 1988, I can attest to the fact that Adam was not the only one in tears. The city mourned.

In 1989, however, it was a different story. The A’s had won the first two games of the Series, beating their cross-Bay rivals, the San Francisco Giants, 5-0 and 5-1, playing in Oakland. On October 17th, Game 3 would be played in San Francisco. I was in my fourth floor office in Berkeley, getting ready to go home and listening to the pre-game broadcast on a portable radio. (Adam was at his home in Florida doing the same.)

Just minutes before the scheduled start of Game 3, a magnitude 6.9 earthquake struck the Bay Area. The building I was in was swaying back and forth so much that I had to hold onto the door jamb to keep from falling over. Not for the first time, I said “Goodbye” to myself.

As often happens when you’re listening to a local radio program during an earthquake, the announcers are feeling it too. Al Michaels said, “I’ll tell you what. We’re having an earth—” at which point the audio cut out. At that point Mary, my office assistant, returned from the ladies’ room. I didn’t ask her for the details; I didn’t need to. She was crying and shaking so badly that I had to hold onto her for a couple of minutes.

Because of the power outage and physical damage to the San Francisco ball park, Game 3 was delayed until October 27th, when the A’s beat the Giants 13-7. The next day, the A’s won 9-6, sweeping the Giants in four games.

Earthquake, schmirthquake. The A’s were champs, I was happy, and Adam was happier. (The following year, the A’s were swept in four games. What goes around comes around, particularly in baseball.)

I remained an Oakland A’s fan and retained my season tickets for a few more years until Adam, no longer in high school, stopped visiting during the summers. He remained a more faithful baseball fan than I ever was. And a better player, too! When he was a young teenager and we were playing softball at a community picnic, I watched him throw out a runner at home from left field on a perfect throw. Years later, when I visited him in Cincinnati during my Walk Across America, I spent the first night watching him play in his Adult League game. He was still a serious player. At some point he told me that he was the Commissioner of his Fantasy Baseball League. Why was I not surprised?

While many people equate Sinaloa, Mexico with the infamous drug Cartel, to me it was the starting point of the memorable Copper Canyon train trip Sharon and I once took. The terminus is the fabled town of Chihuahua. Staying overnight in a motel along the way, Sharon was busy reading a novel, so I wandered into the motel’s TV room adjacent to the lobby. There I found two men my age watching an American baseball game—I think it was the Chicago White Sox. They invited me to join them and gave me a drink. I welcomed it as an opportunity to practice my Spanish. One guy was the hotel manager and the other guy turned out to be the manager of the local bank. They patiently explained to me that Mexicans do not typically follow American teams. Rather, they follow the Mexican players on a variety of American teams. This made sense.

I asked them to define some terminology for me in Spanish so I’d be better able to understand the action: slide; steal; bunt; sacrifice; fly-ball, hit-and-run, etc. We had a great time until Sharon came looking for me. To her surprise, she found me watching Spanish-language American baseball on TV with my new amigos.

The next day as we waited on the platform for our train out of town, I realized that the bank was right across the track. Since we had plenty of time before the train would arrive, we wandered over and walked in. At the end of the long lobby, sitting at a large desk talking with two clients, was my good friend, the bank manager. When he saw me, he beamed a giant smile and came over to greet me warmly, abandoning the poor couple trying to get a mortgage.

I’ve walked into many banks in my life but have never before or since received such a sincere and personal greeting. All because of a baseball game.