The Cities of Refuge: Involuntary Manslaughter, Blood-vengeance, and the Concept of Sanctuary

You’ve certainly heard this old story: One day an elderly man collapses on a sidewalk near Hollywood, and a crowd quickly gathers around him. The fallen man’s wife calls out frantically, “Is anyone here a doctor?”

A tall, well-dressed man steps through the crowd, kneels down and checks the victim’s pulse.

“Oh, doctor, thank God you’re here!” says the woman.

The man looks up and smiles. “I’m not really a doctor. But I play one on TV.”

Shoftim, which means “Magistrates,” discusses legal matters, justice, courts, and other judicial concerns—subjects that might best be addressed by an attorney or a legal scholar. It is found in the book of Deuteronomy. In agreeing to discuss this legal topic, my defense will be that although I am not a lawyer—nor do I play one on TV—I am married to one.

Shoftim discusses the Cities of Refuge, involuntary manslaughter, and blood-vengeance. And to these, I would like to add the concept of Sanctuary. In addition, I hope to reveal how little has changed in the time since this Torah portion was written.

Although the Cities of Refuge are first discussed in some detail in the Book of Numbers (in parashat Masei), Shoftim, in Deuteronomy, provides a more condensed description.

Moses tells the Israelites:

“You shall set aside three cities in the land that Adonai is giving you to possess. You shall survey the distances, and divide into three parts the territory of the country that God has allotted to you, so that any manslayer may have a place to flee to.

“Now this is the case of the manslayer who may flee there and live: one who has killed another unwittingly, without having been his enemy in the past.

“For instance, a man goes with his neighbor into a grove to cut wood; as his hand swings the ax to cut down a tree, the ax-head flies off the handle and strikes the other so that he dies. That man shall flee to one of these cities and live.”

It is further explained that the distances between the cities shall be readily accessible (equidistant from the frontier and each other), “…Otherwise, when the distance is great, the blood-avenger, pursuing the manslayer in hot anger, may overtake him and kill him; yet he did not [deserve] the death penalty, since he had never been the other’s enemy…

“Thus blood of the innocent will not be shed, bringing the bloodguilt upon you in the land that Adonai is allotting to you.”

The parashah continues, “If, however, a person who is the enemy of another lies in wait for him and sets upon him and strikes him a fatal blow and then flees to one of these towns, the elders of the town shall have him brought back from there and shall hand him over to the blood-avenger to be put to death; you must show him no pity…”

Gunther Plaut tells us that the “blood-avenger” represents a leftover of an earlier state of judicial practice. He was usually the slain person’s nearest kinsman, who, by killing the manslayer, would redress the balance of life. Should he in fact succeed in doing so, he would be guiltless, even if the alleged manslayer would later be found to have been innocent; in that case the whole community was considered at fault for not providing a place to which the accused could have fled in time—ostensibly to a city of refuge.

Thus, one could say that the person would flee to a City of Refuge in order to find sanctuary.

Sanctuary refers to a place of protection, for example a wildlife sanctuary. It can also be defined as a consecrated area of a church or temple around its tabernacle or altar. In both ancient and modern terms, it is used to mean a place of safety.

The word “sanctuary” has special meaning to me. I even remember the first time I heard it.

I was a young boy, watching television with my parents. For a moment, let’s hearken back to the days before color television, when TV screens were small, images were grainy, and reception was undependable.

Old movies were often broadcast, and many of these films were classics of the silent era. So, not only did we not have color, often we didn’t even have spoken dialogue.

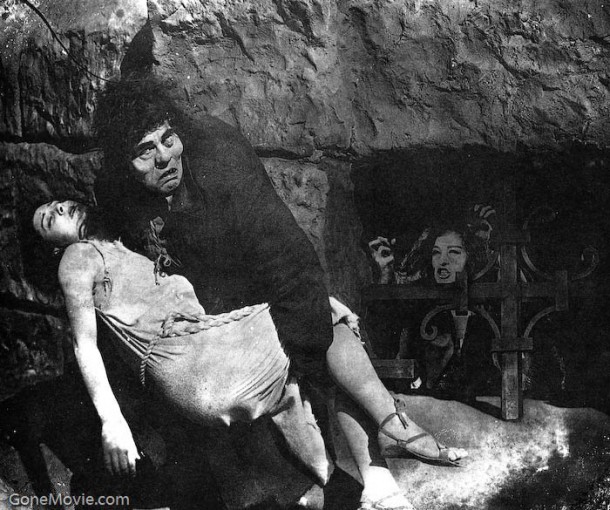

The film we were watching that day was the 1923 silent version of The Hunchback of Notre Dame featuring the celebrated actor, Lon Chaney, Sr., who portrayed the disfigured Quasimodo.

An outcast from society, Quasimodo, is the noble hunchback who rescues the condemned Esmerelda by sliding down a bell tower rope to where she is kneeling on a scaffold, awaiting her execution. He lofts her over his shoulder and carries her to the wide doors of the cathedral. As he enters the holy place, he turns and shouts at the angry mob. Although the words he utters cannot be heard—it’s a silent movie—they immediately appear on the screen in large, capital letters: “SANCTUARY! SANCTUARY!”

I clearly remember turning to my father and mother, asking “What is ‘Sanctuary’?”

(By the way, I was recently able to see this scene again on YouTube. It was still silent, and still in black and white.)

How wonderful it is that a random memory from one’s childhood can be triggered by a passage of Torah!

For those of you who have not read the Victor Hugo novel, or seen one of the many film versions—or even read the Classic Comic book, the story does not end well for Quasimodo and Esmerelda. In order to avoid chaos, the king vetoes the law of sanctuary, and Esmerelda is killed by the troops. Quasimodo murders the story’s villain, and then crawls into the mass grave where Esmerelda is buried. He dies of starvation, his arms wrapped around the only woman who showed him kindness.

Although it failed Quasimodo, the concept of a place of refuge where someone might find sanctuary was certainly a brilliant idea.

In fact, the area around any altar came to be called The Sanctuary. As we know, the Temple in Jerusalem had a sanctuary—the Holy of Holies—where the Ark of the Covenant was located. In most modern synagogues, the main room for prayer is known as the sanctuary.

In many ancient cultures, it was considered a great crime to drag an individual from the Sanctuary or to kill them there. Biblical scholars regard the passages in the Books of Kings where Joab and Adonijah each flee from King Solomon to an altar, as being part of the Court History of David, which they date to the 9th century BCE or earlier.

The principle of sanctuary was adopted by the early Christian church, and various rules developed for what a person had to do to qualify for protection and how much protection was offered.

In England, King Ethelbert may have been the first to issue laws regulating sanctuary around 600 CE.

During the Wars of the Roses (in the mid- to late 1400s), when the Lancastrians or Yorkists would suddenly get the upper hand in a battle, members of the losing side, finding themselves surrounded, would often rush to the nearest church for sanctuary until it was safe to leave it and rejoin their own forces.

When King Edward IV of England died in 1483, his queen, Elizabeth Woodville, the first commoner to marry an English sovereign, took sanctuary at Westminster Abbey, where she and her 6 children enjoyed all the comforts of home. She reportedly brought so much furniture to her sanctuary that workmen had to knock holes in the walls to get all of her stuff inside.

The medieval system of asylum was finally abolished entirely in England in 1623 by James I.

Father Paul Boudreau is a Catholic priest and writer. He told me that the concept of a church as a legal sanctuary from arrest failed to survive in Europe past the 17th century, and suggests that this may be one of the reasons why it was never adopted in the United States.

He did point out, however, that the “New Sanctuary Movement” that emerged here in the 1980s was an expression of the church’s ministry of social justice, often protecting Latin American immigrants escaping civil unrest and political persecution. Many were given shelter and protection in churches across America, and although the government had every right to enter and arrest the suspects, it avoided a dreadful public relations situation by not doing so. Although some church leaders were arrested they were given nominal fines or light sentences that were typically suspended.

Father Paul was quick to remind me that the City of Oakland was one of those officially declaring itself a “Sanctuary City.” A Christian Science Monitor article I found from September 2007 reports:

When responding to an incident, Oakland police will gather the usual “who, what, and when” of those involved. But there’s one question they won’t ask: “Are you here in this country legally?” That’s because Oakland is one of the dozens of sanctuary cities across the United States that have policies directing local police or officials to stay out of immigration matters.

Since Oakland so rarely gets any good press at all, it’s nice to read such things about my city. And social action has been a cornerstone of Temple Sinai, the congregation to which I belong, for many years.

Father Paul Boudreau then quoted some pertinent scripture to support Catholic social justice teaching. First, in Leviticus: “When a stranger resides with you in your land, you shall not wrong him. (He) shall be to you as one of your citizens; you shall love him as yourself, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt…” And then, in the Book of Numbers, which specifically tells us that the sanctuary law protects not only the Israelites but all the “resident or transient aliens” among them.

My good friend, scholar and writer Alice Camille, also shared with me her thoughts on sanctuary. Theologian Richard McBrien, she wrote, says that in Catholic tradition “The right of sanctuary is rooted in the reverence for places of worship and an abhorrence of any violation of sacred space.”

This suggests that our idea of sanctuary necessarily depends on our understanding of sacred space (including our own synagogue sanctuary and chapel.) Alice Camille goes on to say that if contemporary worship areas are viewed only as “gathering rooms for the already convinced,” we risk losing that sense of “God-space” that the ancients had. She asks, “If a place isn’t seen as God-haunted in that primeval way, what’s to violate, and why not cross the line?”

I love her use of the phrase “God-haunted,” which should certainly ring true with the Jewish people, who have a strong oral and literary history of mysticism as reflected in both Kabbalah and the many myths and legends that permeate the fabric of the Jews.

Alice emphasizes that there is a real Presence of God in a place of worship, where a perpetual lamp burns nearby to affirm that the light of the world is at home for those who come calling. Thus, the Ner Tamid—the Eternal Light, may be viewed not only as a symbol of holiness, but as a reminder that this holy place can be viewed as a place of sanctuary as well.

In his article “Cities of Refuge and Cities of Flight,” Rav Amnon Bazak says that parashat Masei refers to the Cities of Refuge as a detention center until the manslayer is brought to justice, as well as a sort of prison where the slayer must stay—even against his will—until the death of the Kohen Gadol. So while he benefits from the protection the City provides him from the threat of the blood-avenger, the city also serves as a punishment for him; even if he wishes to leave, he may not.

In contrast, Rav Bazak says, in parashat Shoftim the City of Refuge is not a punishment, but rather a privilege, and serves as a place of protection for unintentional slayers, each of whom is being pursued by an avenger who seeks to kill him. Society is therefore obligated to shelter these individuals.

While legal experts assure me that the term “involuntary manslaughter” can be extremely complicated, for our purposes, I will keep it simple:

Involuntary manslaughter is the unlawful killing of another human being without intent. The absence of intent is the essential difference between voluntary and involuntary manslaughter. Also in most states, involuntary manslaughter does not result from a heat of passion but from an improper use of reasonable care or skill while in the commission of a lawful act.

A jury verdict of involuntary manslaughter is not necessarily unexpected, but it is certainly emotionally-charged. “Blood-vengeance” can often be felt in the emotions of family members of those who are killed. Communities are often torn apart by such incidents.

One scenario is very personal and painful for me. On June 5, 2003, my cousin, Matthew Sperry, was riding his bicycle to work in Emeryville. He was a wonderful young man and a talented musician who had performed with both Tom Waits and Anthony Braxton. A woman driving a pickup truck, turned a corner and ran over him, killing him. Matthew left behind a wife and young daughter. A “ghost bicycle” was placed at the location of the accident, serving as a memorial to Matthew.

When I later spoke to his widow, she told me that because there were no witnesses to the incident, and since “no crime” was being committed during the course of the accident, the driver was not convicted of manslaughter. (It seems that driving without a current and valid driver’s license was not considered a crime in this case.) Perhaps a trace of blood-vengeance remains in the hearts of many family members and friends who knew Matthew.

So, the more I ponder the concept of sanctuary, the Cities of Refuge, involuntary manslaughter, and blood-vengeance, I see how little has changed from the days when the Torah was written.

One day as we sat in our living room, I posed the following scenario to my wife Sharon, the attorney:

Let’s imagine that two good friends are on a camping trip, and one of them is chopping firewood for their campfire. As his hand swings the camp axe, the axe-head flies off the handle and strikes the other and kills him. An identical situation to what is described in Deuteronomy.

Given the nature of our society, I asked her, what might happen next? And here’s what we came up with: The incident is investigated by the police. The man’s grieving widow is represented by a team of attorneys. It is discovered that the camp axe involved in the accident contained a manufacturing defect.

This tragic story is reported in the media, and other victims come forward. There is a class-action lawsuit against the axe manufacturer.

Not too difficult to imagine, is it? A Google search revealed this:

July 3, 1997, For Immediate Release – Washington, DC

In cooperation with the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission, The Coleman Company, of Wichita, Kansas, is recalling 20,000 camp axes. The axe handle could crack or break during use, causing the axe head to separate from the handle. Consumers could be injured if they are hit by the separated axe head… The Coleman Company has received two reports of the axe heads separating from the handles. No injuries have been reported.

Fortunately, no injuries. No deaths. No involuntary manslaughter. No blood-vengeance. And no need to flee to a City of Refuge to seek sanctuary.

Originally delivered as a drash (sermon).

Leave a reply